A team of researchers from the University of Nottingham in the UK and the University of Ulm in Germany has identified a new hybrid state of matter that blends characteristics of both solids and liquids. This groundbreaking discovery could have significant implications for catalysis and various thermally-activated processes.

Traditionally, the distinction between solid and liquid phases has been viewed as clear-cut. In liquids, atoms move fluidly, while in solids, they maintain fixed positions. Solidification occurs when random atomic motion transitions into an ordered crystalline structure. However, recent findings suggest that this simplistic view is incomplete. The researchers utilized advanced microscopy techniques to reveal that liquid metal nanoparticles can contain stationary atoms, which play a crucial role in the solidification process.

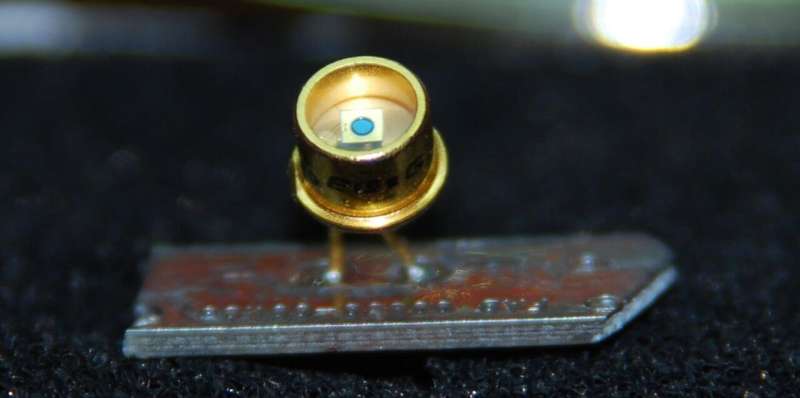

Led by Andrei Khlobystov, the research team employed spherical and chromatic aberration-corrected high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (Cc/Cs-corrected HRTEM) at the low-voltage SALVE instrument in Ulm. They studied melted metal nanoparticles, including platinum, gold, and palladium, deposited on a thin layer of graphene. This carbon-based material served as a heating substrate for the nanoparticles.

During the experiments, Christopher Leist, who oversaw the HRTEM experiments, noted, “As they melted, the atoms in the nanoparticles began to move rapidly, as expected. To our surprise, however, we found that some atoms remained stationary.” The research revealed that these stationary atoms strongly bind to defects in the graphene support at elevated temperatures.

Remarkably, when the electron beam from the transmission microscope increased the number of these defects, the quantity of stationary atoms within the liquid also rose. Khlobystov explained that this phenomenon significantly alters the crystallization process. With fewer stationary atoms, a crystal grows directly from the liquid. Conversely, an increase in stationary atoms disrupts crystallization, resulting in an absence of crystal formation.

The researchers observed that when stationary atoms formed a ring around the liquid, the atoms within the droplet remained in motion, even at temperatures below the liquid’s freezing point. This unique state challenges long-held assumptions about the behavior of materials in different phases.

The Nottingham-Ulm team originally set out to investigate metal nanoparticles for catalysis applications, funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC). Khlobystov elaborated, “Our approach involves assembling catalysts from individual metal atoms, utilizing on-surface phenomena to control their assembly and dynamics.” He emphasized that understanding how metal atoms behave at various temperatures and environments is essential for controlling particle size and structure.

The research team faced considerable challenges in identifying a suitable support material for the metal. Graphene proved to be an ideal candidate due to its thinness, robustness, and thermal conductivity. Additionally, they successfully manipulated defect sites around each particle using the electron beam, turning the TEM into a dual-purpose tool for both imaging and environmental modification.

Looking ahead, the researchers aim to explore the potential applications of this hybrid state in catalysis. Khlobystov noted the importance of enhancing control over defect production and scaling these findings. Furthermore, they expressed interest in studying the behavior of corralled particles in a gas environment to better understand how reaction conditions influence this phenomenon.

The full findings of this research are reported in the journal ACS Nano. This work not only pushes the boundaries of material science but also opens new avenues for future technological advancements.