Protests have played a crucial role in shaping societies, from the streets of London to the squares of Eastern Europe. In a recent discussion, experts Danny Bird, Katrina Navickas, and Timothy Garton Ash explored the evolution of protests, their legal definitions, and the impact they have had on political change. Understanding what constitutes a protest, as opposed to a riot or revolution, is essential in grasping its significance in various historical contexts.

Historically, a protest is often defined legally, making its interpretation fluid. According to Katrina Navickas, a professor of history at the University of Hertfordshire, the earliest legal definition in England and Wales dates back to the 1714 Riot Act, which differentiated a riot from peaceful protests. The concept evolved further in the 19th century with the rise of democratic movements when public gatherings became a means for collective claims and political engagement.

In contrast to violent revolutions, modern protests tend to emphasize nonviolent action. Timothy Garton Ash, a professor at the University of Oxford, cited historical examples such as Mahatma Gandhi in India and the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, highlighting how these movements effectively used peaceful demonstrations to drive change. The pivotal 1989 revolutions in Eastern Europe represent a unique intersection of nonviolence and revolutionary change, showcasing the power of collective public action.

While timing and tactics are essential in determining the success of a protest, context also plays a significant role. According to Garton Ash, successful movements often require favorable internal and external conditions. The 1989 revolutions succeeded where many protests during the Arab Spring faltered due to differing circumstances. Effective protests are strategic, not mere expressions of anger, and aim to influence those in power.

Despite the right to protest being a hallmark of free societies, it often generates unease. In Britain, for instance, the lack of a statutory right to assembly until the Human Rights Act of 1998 meant that protests were not guaranteed but rather permitted. Throughout the 20th century, legislation frequently targeted specific groups, reflecting ongoing tensions between free expression and public order, illustrated by the debates surrounding Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists in the 1930s.

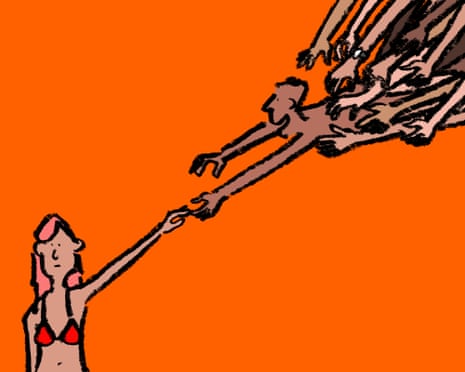

In contrast, authoritarian regimes tend to view protests as threats. Garton Ash describes a pivotal moment in Leipzig during the autumn of 1989, where an initial small demonstration grew rapidly, showcasing the “cascade effect” of critical mass. This phenomenon terrifies authoritarian leaders, as it demonstrates the potential for collective dissent to overpower fear.

The historical narrative of Britain is often portrayed as one of gradual evolution rather than revolution. Navickas argues this perspective neglects the harsh realities faced by many, particularly in Ireland, where extreme measures were implemented to suppress dissent. The struggles of the Tolpuddle Martyrs and the Bloody Sunday massacre in Ireland exemplify how state violence can galvanize broader support for movements.

The regulation of protests has varied over time, with laws often targeting specific movements rather than broadly applied public order legislation. In the 19th century, legislation was notably reactive, responding to the Chartists, trade unions, and suffragettes. Recent laws have arisen in reaction to movements focused on environmental issues and civil rights, reflecting a historical continuity in Britain’s approach to managing dissent.

The spaces in which protests occur also shape their impact. Protests assert claims to public space, with significant events often held in symbolic locations. Iconic sites such as Trafalgar Square and Hyde Park have witnessed protests that challenged authority and reshaped public narratives. The use of public squares as stages for political theater is evident in events like the Tiananmen Square protests and the Velvet Revolution in Prague, where the physical setting amplified the message of dissent.

The legacy of protests often hinges on their outcomes. Movements that succeed, like the suffragettes, are integrated into the national narrative as justified, while those that fail may be forgotten. This selective memory can shape public perception of historical events, as seen in the contrasting recognition of violent tactics employed by different groups throughout history.

Class dynamics have also influenced the success of protests. Movements led by well-connected individuals, such as the abolition of slavery, often achieved legislative change more easily than working-class movements, which faced greater challenges in gaining visibility and resources. However, when protests unite across class boundaries, they often prove more effective, as seen in the Solidarity movement in Poland during the 1980s.

Today’s protesters can learn valuable lessons from their predecessors. Achieving critical mass, maintaining nonviolence, and developing a clear strategy are essential for effective movements. As Garton Ash noted, understanding history is crucial for navigating the complexities of modern protests. By studying past successes and failures, activists can better strategize their approaches to create meaningful change in the face of contemporary challenges.

As the landscape of protest continues to evolve, the insights gleaned from historical movements remain relevant, guiding today’s activists in their quest for justice and social change.