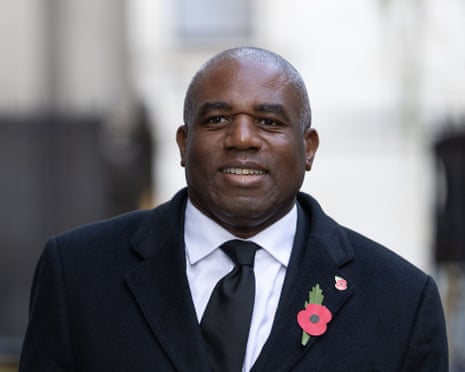

David Lammy, the United Kingdom’s Justice Secretary, is reconsidering his proposals to significantly alter the jury trial system. Initially, he aimed to restrict jury trials to the most serious charges, such as murder and rape. However, following feedback from cabinet members, Lammy now appears inclined to maintain jury trials for more serious offences while still reducing their availability for lesser charges.

In a report by the retired senior judge Sir Brian Leveson, it was recommended that “either-way” offences, which could result in sentences of three years or less, should be handled by magistrates’ courts or a new judge-only division. This recommendation aligns more closely with Lammy’s current proposals, which are set to be presented to Parliament later this week.

A leaked memo from last week indicated that Lammy was contemplating even more extensive changes, suggesting that jury trials might only apply to public interest offences with potential prison sentences exceeding five years. This plan could have removed the long-standing right for many defendants to have their cases heard by a jury.

The Justice Secretary has characterized the existing backlog in the court system as a “courts emergency,” with over 100,000 cases pending. He expressed concern that victims are left waiting for justice, prompting the need for reform.

In an interview with Sky News, Lammy stated, “Where should the threshold be? [Leveson] suggested it should be three years … and that’s what I’m looking at.” Under this threshold, more serious offences beyond murder and rape would still be tried by juries, while lesser offences such as minor assaults and thefts could be managed by magistrates or judge-only trials.

Cabinet discussions have influenced Lammy’s evolving stance on the proposals, suggesting that there may have been internal opposition to the radical reforms. He described the feedback process as a “process question,” reiterating the importance of cabinet consultations in shaping his final judgment.

Lammy emphasized his belief in the jury system, thanking the approximately 300,000 individuals who serve on juries each year. “It’s fundamental in our system,” he stated. “I’ve stood up for juries all of my life, but I don’t want the system to collapse. I want it to continue.”

The proposed changes have drawn criticism from various legal professionals, including the Criminal Bar Association and the Bar Council. They argue that there is no justification for restricting the right to a jury trial from both a principle and practical perspective. Under the new proposals, juries would only hear the most serious cases and lesser “either-way” offences when deemed appropriate by a judge.

The Law Society of England and Wales has expressed skepticism regarding the effectiveness of these reforms in reducing the backlog. Keir Monteith KC, a criminal barrister, criticized Lammy’s shift towards judge-only trials, calling it unconstitutional and potentially leading to more injustices for minority ethnic defendants.

According to data from the Ministry of Justice, nearly half of the outstanding cases involve alleged violent and sexual offences, while only about 3% of criminal cases currently involve a judge and jury.

In a separate matter, Lammy confirmed that two prisoners remain at large after being mistakenly released. He did not provide additional details regarding the circumstances surrounding their release.

As Lammy prepares to address Parliament, the legal community and the public await clarification on the future of jury trials in the UK justice system.