A recent study indicates that the weight loss injection Mounjaro may significantly reduce food cravings by altering brain activity associated with eating control. The findings suggest that this injection could play a crucial role in managing obesity and diabetes. Approved by the NHS for treating type 2 diabetes and obesity, Mounjaro is expected to be administered to 240,000 individuals over the next three years.

The primary component of Mounjaro is tirzepatide, a drug that belongs to the class of medications known as GLP-1 receptor agonists. These drugs mimic the effects of the naturally occurring hormone GLP-1, enhancing insulin production, lowering blood sugar levels, slowing digestion, and ultimately reducing appetite. Many patients have reported that Mounjaro helps diminish persistent thoughts about food, often referred to as “food noise.”

Despite these anecdotal reports, comprehensive research on Mounjaro’s effects on brain activity has been limited. In a pioneering study conducted in the United States, researchers implanted electrodes in the brains of three severely obese patients to examine the drug’s influence on areas linked to pleasure and reward. This innovative approach allowed for direct observation of brain activity related to food cravings.

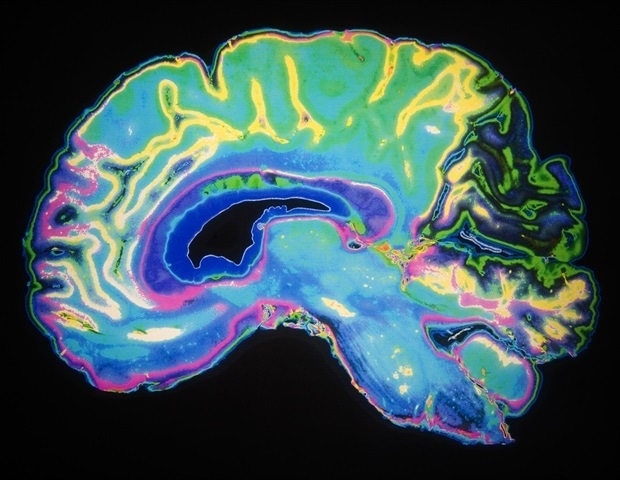

The researchers discovered that episodes of intense preoccupation with food correlated with low-frequency brain signals, known as delta-theta activity, specifically in the nucleus accumbens—a key region in the brain’s reward system. In two of the patients, electrical stimulation to specific brain areas reduced this brain signal. The third patient, who had undergone weight-loss surgery and was treated with Mounjaro for diabetes management, also exhibited decreased food cravings and a decline in delta-theta brain activity while on the medication.

Despite these promising results, researchers noted that the reduction in cravings and brain signal activity returned after a few months. This raises questions about the long-term efficacy of Mounjaro in managing food cravings.

Dr. Simon Cork, a Senior Lecturer in Physiology at Anglia Ruskin University, cautioned against overgeneralizing the findings. He emphasized that the research focused on a specific marker of brain activity linked to binge eating, a condition not representative of the broader population of individuals with obesity. “We know from animal studies that directly record from neurons in this region of the brain that GLP-1 does suppress activity of this region of the brain, and this suppression is likely associated with the reduction in ‘food noise’ that patients with obesity often report,” Dr. Cork stated.

He added that while the study’s methodology is intriguing, it is essential to recognize the limitations inherent in examining only a small group of patients with a unique condition.

The findings of this study were published in the journal Nature Medicine, contributing to the growing body of research on the mechanisms underlying obesity treatments. As the understanding of how Mounjaro and similar medications affect brain function continues to evolve, further studies will be crucial in determining their long-term implications for weight management and overall health.